Michael Owen has launched a passionate defence of his career, insisting that his teenage rise at Liverpool placed him on a pedestal that few English players including Wayne Rooney have ever reached.

The former England striker, now 45, has found himself at the centre of social media debates in recent weeks, with fans comparing his impact as a teenager to Rooney’s.

Both burst onto the scene at a young age, both carried the hopes of England, and both are remembered as generational talents. But speaking on the Rio Ferdinand Presents Podcast, Owen argued that his teenage achievements remain unrivalled, even if injuries later robbed him of his prime.

“People will have only seen me or remember me in the later years when I’m getting worse and worse and worse and worse and worse,” Owen said.

“The agony for me is that nobody remembers. Only a few people remember what I was like when I was ten and 12 and 15 and 18 and maybe up to 22.

“I was past it and on the way down by 21 or whatever. That’s the agony because was there another 18-year-old that was anywhere near me at 18? I was light years clear of anything in my age group, anything in England.”

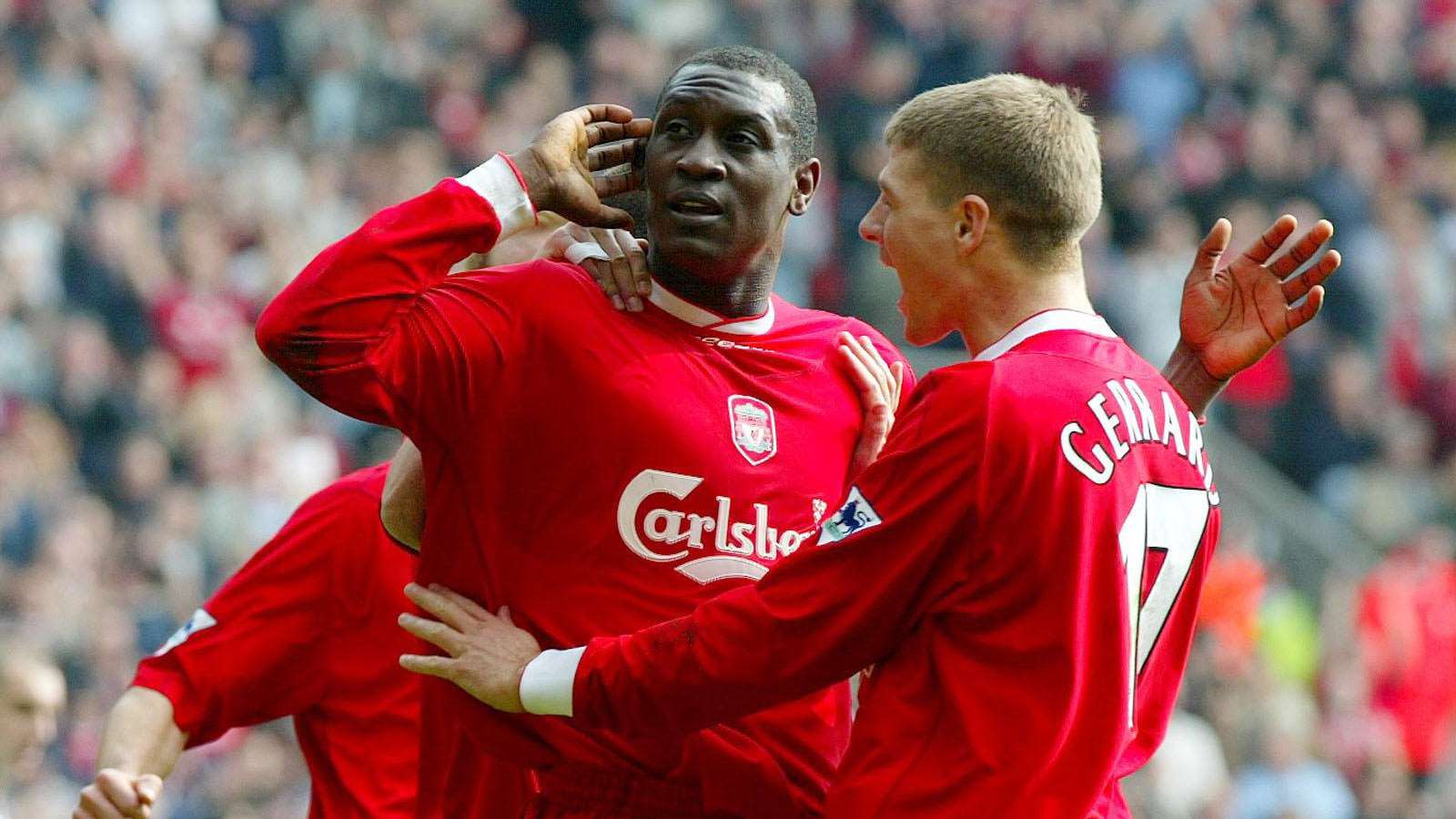

Owen’s words carry weight when you consider his trajectory. In May 1997, a 17-year-old Owen scored on his Liverpool debut against Wimbledon. By the following season, he was the club’s leading forward, his explosive pace and ruthless finishing making him a household name. He won the Premier League Golden Boot at just 18, something no teenager has replicated since.

“You can bring the next kid and the next kid and the next kid and the next one that scores ten goals and everybody’s like: ‘Oh, it’s the next Michael Owen’,” he recalled.

“But I was competing against great strikers. Now there’s like four, five good strikers in the Premier League.”

Owen wasn’t exaggerating. His teenage years saw him not only carry Liverpool but also England, scoring a stunning solo goal against Argentina at the 1998 World Cup — an iconic moment that announced him to the world stage

Yet, as Owen himself admits, his body betrayed him early. Persistent hamstring injuries curtailed his acceleration, the very weapon that made him so devastating.

“People can look at how I played at 26 and say, ‘these players are much better than him.’ Yes, I know. By then, my hamstring muscles were torn in half,” Owen explained.

“I was ashamed to wear a shirt with my name on it at 26 and beyond. I was already in decline. I won the Ballon d’Or when I was already on the downturn. It was a serious decline. At 19, my muscles tore in half.”

By his mid-20s, Owen was a different player. Though he would still enjoy spells at Real Madrid, Manchester United, and Stoke, his explosive pace never returned.

What lingers, he says, is the frustration that people only remember the latter stages of his career.

“At 17, I became the Premier League top scorer – that will never happen again”

Owen’s numbers at Liverpool underline his point. In eight years at Anfield, he scored 158 goals in 297 appearances, lifting the FA Cup, two League Cups, the UEFA Cup, and the UEFA Super Cup. His crowning individual moment came in 2001, when he won the Ballon d’Or at just 22 years old — making him only the fourth Englishman to claim the prestigious prize.

Yet even that award, Owen insists, came when he was already past his physical peak.

“I won the Ballon d’Or when I was already on the downturn,”

He admitted, underlining the sense of what might have been had his body held up.

Wayne Rooney, meanwhile, made his own sensational breakthrough as a 16-year-old at Everton, scoring against Arsenal in 2002 before becoming England’s talisman at Euro 2004. His career would span more than a decade at Manchester United, where he became the club’s all-time leading scorer.

But for Owen, the debate is not about longevity, but about teenage brilliance. And on that front, he believes his case is watertight.

Reflecting on his journey, Owen said the frustration is simple: “That’s the agony — because nobody remembers.”

Michael Owen may not have enjoyed the same career longevity as Rooney, but his words remind football fans of the teenager who once terrified defenders across Europe. His legacy, he argues, should be measured by what he achieved before injuries struck